On August 5, a follow-up meeting was held for Agreement 13/Cooperation Agreement 95 (TA13/TC95) between BIREME/PAHO/WHO and the General Coordination of Documentation and Information of Brazil’s Ministry of Health (CGDI/SAA/SE/MS) in coordination with PAHO Brazil.

The purpose of the meeting was to present the technical and strategic advances of the first half of 2025 in the context of three Expected Results (ER) and to revisit the work plan, reaffirming the joint commitment to modernization, innovation, and strengthening of health information and knowledge management in Brazil.

Innovation in Technical and Scientific Information Sources (ER 1)

The consolidation of DeCS Finder AI was highlighted, a tool based on artificial intelligence that automatically suggests descriptors from the DeCS thesaurus (DeCS represents the acronym in Portuguese for Health Sciences Descriptors) for cataloging scientific documents. Currently in advanced testing, the solution is already integrated with systems such as FI-Admin and Annif, with a focus on streamlining indexing, ensuring greater standardization and quality of records, and supporting cooperating centers with small teams.

The planning of the use of natural language models for search services and narrative syntheses in the VHL was also highlighted. The so-called Super Abstracts, which offer short descriptions of documents, are already in use in 100% of the Mosaico database and 50% of LILACS, expanding the possibilities for easy access to information.

Another relevant advance was the start of the SOPHIA system data collection process, allowing for integrated updating of the Ministry of Health VHL indexes. At the same time, the BiblioSUS Network contributed 1,392 documents in just six months, reinforcing the expansion of bibliographic control of the scientific output of Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS).

Strengthening the Brazilian VHL Network (ER 2)

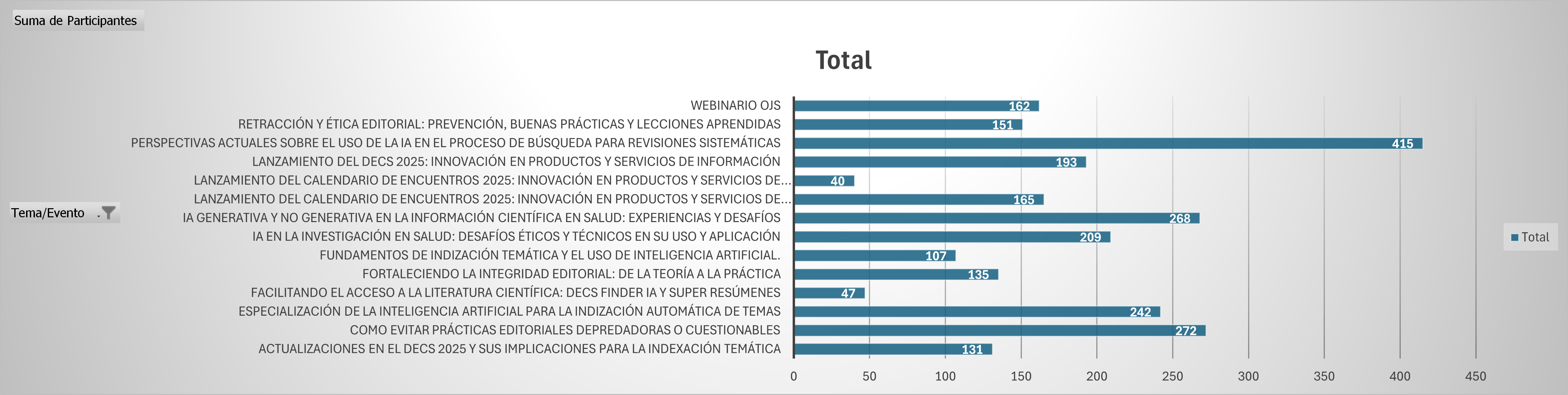

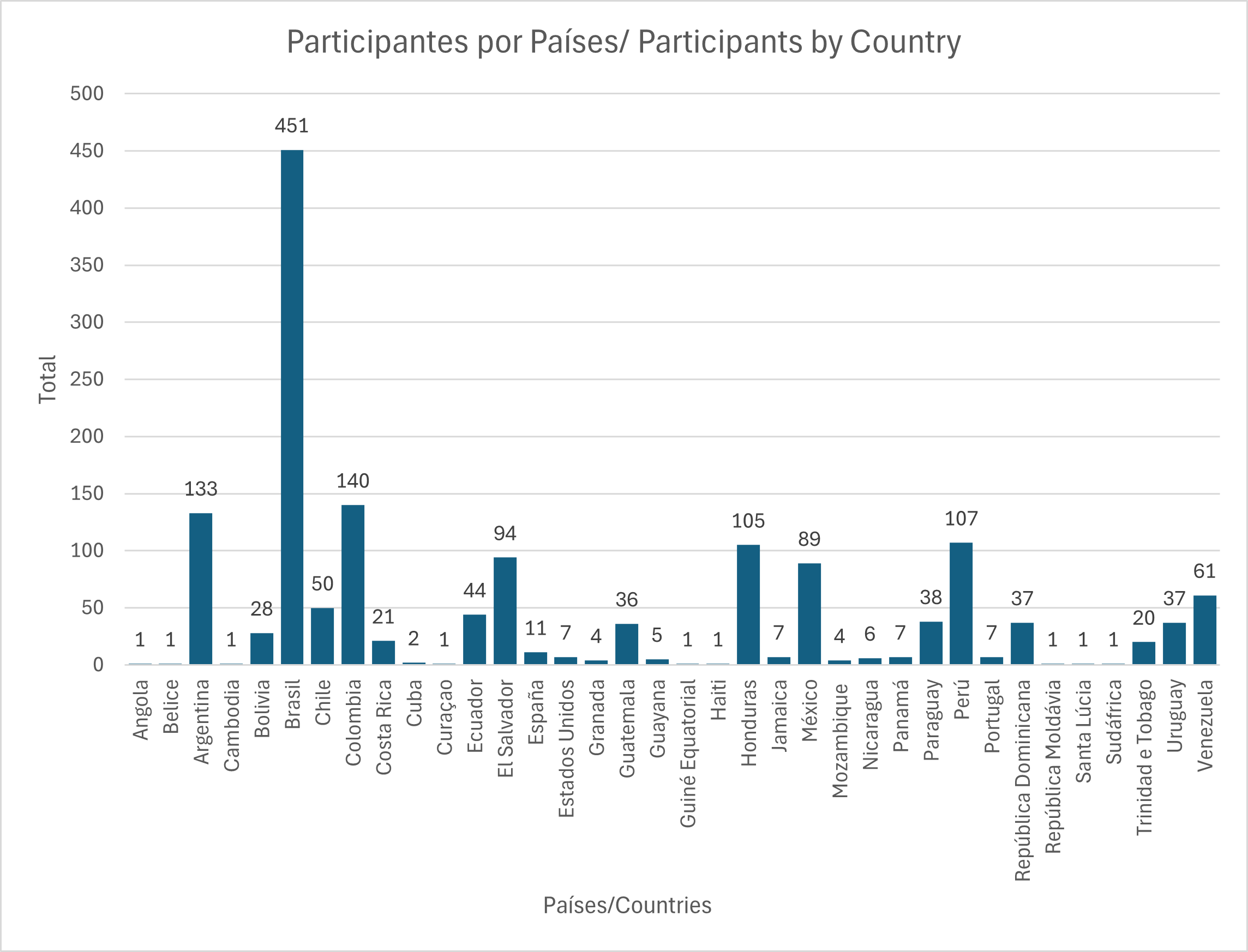

Within Brazil VHL Network, training activities advanced with 10 virtual meetings held, bringing together an average of 170 connections per session, with participation from 36 countries. Topics included document indexing according to the LILACS methodology, good editorial practices in scientific journals, and innovation in information products and services.

The Network’s documentary contribution was also significant: 715 new records were added to LILACS between January and July 2025, in addition to maintaining a total database of 1.191 million documents, of which 700,000 came from Brazil, with the active participation of 390 cooperating centers. The ColecionaSUS database totals 39,819 records from 124 cooperating centers.

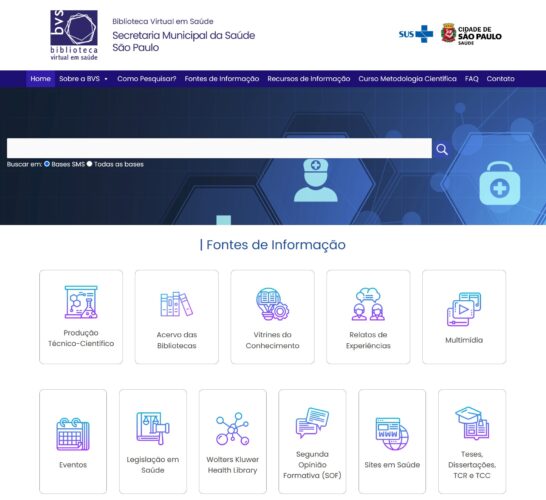

Among the modernization actions, the launch of the new Ministry of Health VHL portal and the progress in updating the BiblioSUS Network and VHL Stations platforms stood out, in addition to the integration of Health Economics – ECOS VHL with a new collaborative interface. The registration update of cooperating libraries and centers reached 310 active institutions in 2025.

The National Meeting of the Brazil VHL Network is scheduled to take place in November 2025 with the XXIII National Seminar on University Libraries (SNBU 2025) in São Paulo, Brazil, which will also acknowledge LILACS 40th anniversary.

COVID-19 Pandemic Memorial Portal (ER 3)

The COVID-19 Pandemic Memorial Portal project has progressed steadily. Carried out in technical cooperation between BIREME, the Ministry of Health and experts, the portal aims to preserve and disseminate collections of documents, interviews and testimonials about the pandemic, transforming them into a space for memory, reflection, and collective learning.

Among the main results achieved are the definition of the scope, target audience, and governance model of the portal; the holding of strategic meetings and technical visits, including to the Public Archives of the State of São Paulo (APESP); and the initial mapping of the collections that will comprise the archive. In this process, guidelines for the curation and digital preservation of content were developed.

In the technological field, the installation and configuration of the Archivematica and Tainacan platforms stand out, which will be responsible for the preservation and publication of the portal’s content. The development of the website also advanced with the application of user-centered dynamics (UX Design), which resulted in an initial menu proposal, a low-fidelity conceptual prototype, and usability guidelines that will guide the thematic organization, navigation, and user experience.

Communication activities began to take shape with the dissemination of multilingual content, the integration of teams through collaborative channels and the publication of articles in BIREME’s Bulletin and other PAHO/WHO communication channels. These initiatives have increased the visibility of the project and strengthened the exchange of information and monitoring of progress by partner institutions.

Perspectives

At the end of the meeting, the teams acknowledged that progress was only possible thanks to ongoing dialogue and integrated work between BIREME, CGDI/Ministry of Health and experts. The expectation is that the second half of 2025 will be marked by new milestones in cooperation, consolidating both the modernization of information sources and the creation of innovative spaces for collective memory and network strengthening.